The intersection of morality and aestheticism in Lolita and The Picture of Dorian Gray

Nabokov blurs boundaries between aestheticism and morality to inoculate readers against Humbert Humbert’s paedophilia and solipsism, whereas Wilde uses aestheticism to elucidate Dorian Gray’s vanity.

Both books attempt to perpetuate a boundary between the moral and the aesthetic, albeit for different reasons. Nabokov and Wilde share similar views about art, apparent in Wilde’s preface and Nabokov’s afterword.

Wilde viewed his life as a work of art and asserts that ‘all art is quite useless’ in his preface, suggestive of Wilde’s polarity between aesthetics and morals. In his interview with Playboy, Nabokov remarks, ‘what makes a work of fiction safe… is not its social importance but its art, only its art,’ clarifying Nabokov’s polarity between aesthetic and moral value; he believed Wilde to be a ‘dainty poet’ and a ‘rank moralist’ thus we can infer Lolita is not a didactic novel (Playboy, 1964). Comparatively, The Picture of Dorian Gray is regarded for its philosophical and moral value although Wilde’s epoch-defining novella didn’t intend its moral reception, Wilde prefaces the novella with an establishment of the boundary between morality and aestheticism through his assertion that ‘all art is quite useless’ and reinforces this boundary: “vice and virtue are to the artist materials for an art” we can infer Wilde regards the morality of his characters as a tool for his narrative rather than conveying a moral proposition. Nabokov’s afterword doesn’t establish any boundaries between aestheticism and morality thus, we cannot regard Lolita as a didactic novel. Nabokov’s use of an afterword to elucidate the boundaries between the aesthetic and the moral reinforces Nabokov’s disregard for the ethical implications of Lolita.

Despite differing authorial intent, the books share aesthetic similarities, the surreal tone created and maintained throughout the novel through numerous references to nature. Pinder writes that Wilde ‘hits us over the head with a laburnum branch…symbolic of forsaken, pensive beauty’ from which we can infer Wilde’s use of natural imagery is a recurring motif representing Dorian’s beauty throughout the novella (Floral Arrangements in Dorian Gray, 2018). Wilde references to nature to perpetuate the aesthetic value of flowers and their sensory indulgence (Floral Arrangements in Dorian Gray, 2018). In contrast, Nabokov refers to nature and maintains the surreal ambience to deceive the reader into only knowing the ‘safely solipsised’ version of Dolores, the sibilance mimicking the hissing of a snake, which appears as Lolita (p.60). Upon reading Lolita for the first time, it is apparent that the novel is a spiderweb of literary devices; Nabokov characterised Lolita as a record of his love affair with the English language (p. 316) it is apparent Nabokov’s primary intent is to deceive the reader in an infinite game of cat and mouse (p. 316) with layers upon layers of literary allusions. For those reading Lolita for the first time, it appears the boundaries between the moral and aesthetic blur structurally because there's a double narrative going on, Humbert Humbert’s narrative and Nabokov’s narrative behind the meticulously placed literary devices cancelling one another out, manifesting in a lack of boundaries between the aesthetic and the moral. Nabokov attempts to distract the reader from the grotesque reality of H.H. 's actions and perpetuate the ‘safely solipsised’ perception of Dolores Haze through his use of aesthetics (p.60). Comparatively, the aspects of aestheticism present in The Picture of Dorian Gray are incorporated with aesthetic appreciation, and the boundaries between aestheticism and morality are explicit; Wilde popularised the aestheticism movement of the late 19th century, which emphasized the aesthetic value of literature and blissful ignorance of the immorality in life. Nabokov remarks:

“Literature was not born the day when a boy crying "wolf, wolf" came running… born on the day when a boy came crying "wolf, wolf" and there was no wolf” (Nabokov, Lectures on Russian Literature)

His statement implies that literature is written with the intent to deceive. The protagonists of both narratives share several characteristics, cultivating an almost pathological narcissism, and both writers highlight immoral aspects of their protagonists using doppelgangers. A crucial structural difference, Dorian Gray’s narrative is told from a third-person perspective; Humbert’s narrative is told from his perspective in first-person despite H.H. having ‘incomplete and unorthodox memory’ implying that Humbert is an unreliable narrator (p.217). This allows Nabokov to implicitly manipulate readers, whereas Wilde’s use of third-person allows readers to understand the implications of Dorian’s immorality and debauchery. Both protagonists disregard the feelings of others and egocentrically approach their problems i.e. Humbert addresses his readers as ‘the jury’ and structures his ‘memoir’ to be used as a defence for those overseeing his court case. Both share a hedonistic worldview and infatuation with youth which Nabokov and Wilde illustrate with doppelgangers, despite utilising the literary device with differing impacts.

With Dorian’s portrait as his doppelganger, Wilde uses the portrait to elucidate Dorian’s immorality; Nabokov uses the character of Clare Quilty as Humbert’s doppelganger to perpetuate aspects of parody found in the novel, undermining the sexually grotesque themes addressed due to the comic presence looming throughout the novel; the doppelganger demonstrates different vices attributed to the human psyche. In his essay about the duality of doppelgangers, Faurholt asserts the doppelganger has ‘two distinct types’ entailing ‘the alter ego of a protagonist… perpetrated by a mimicking supernatural presence’ and ‘an unleashed monster…a physical manifestation of a dissociated part of the self’ (Double Dialogues, 2009). Wilde presents this with Dorian’s doppelganger being his portrait and supporting the former of the two types, acting as ‘a mimicking supernatural presence’ due to significant changes appearing each time Dorian commits an immoral action. Conversely, Humbert’s doppelganger, Clare Quilty, is antagonised by Humbert Humbert, thus conforming to the latter of the two types - ‘an unleashed monster’ - a magnification of Humbert Humbert’s actions to the highest degree. Humbert’s ‘moral apotheosis’ (worded by fictional John Ray. Jr, p. 5) occurs too late; his words in the final chapter rub salt in the wound of Dolores’ untimely death: “the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that concord” (p. 308).

Wilde uses the doppelganger as a literal reflection of Dorian’s immorality, clarifying the contradiction between appearance and reality and reinforcing this through the third-person perspective. In contrast, Nabokov uses the doppelganger as a hyperbolic representation of Humbert’s actions with no incongruity between Humbert’s appearance and his reality thus being an unreliable narrator. Nabokov dichotomises self-conscious intellectual (Humbert Humbert) and a perverted paedophile (Clare Quilty) thus, Nabokov uses first-person perspective to blur boundaries between appearance and reality, impeding readers from wholly understanding the moral implications of Humbert’s actions. Wilde retains the terror associated with the doppelganger; the ‘split personality’ through Dorian’s denial regarding his immoral actions, which serve the purpose of confronting and reconciling with the ‘dissociated part of the self’ (Double Dialogues, 2009) as Dorian acknowledges his spiritual attachment to the painting: ‘It had revealed to him his own body… it would reveal to him his own soul’ (p. 90). Wilde foreshadows and thus coalesces the notion of the painting as ‘an alter ego’ and a ‘split personality’ (Double Dialogues, 2009) as Wilde’s use of the nouns ‘body’ and ‘soul’ suggests the painting is a part of Dorian, foreshadowing the final chapter; there is a visible contrast between the appearance and the reality of Dorian’s beliefs revealed to him by ‘his own soul’ and his actions revealed to him by ‘his own body’. Dorian does not murder the portrait it is - as Wilde suggests with the verb ‘reveal’ - a revelation which Dorian reaches at the end of the novella.

Nabokov utilises the method of parody often throughout the novel to his detriment as it downplays the grotesque themes of the novel, presenting the doppelganger as comical. Humbert doesn’t acknowledge Quilty as his equal but refers to him as a ‘red-beast’ and a ‘red fiend’ antagonising Quilty, while Nabokov’s association of Quilty with the colour red parodies the stereotypical caricature of Satan. Nabokov uses red throughout Lolita, but the several variations of the colour hold significance to H.H.’s psyche, in this context, indicating anger. Both authors use colour imagery in their works, some colours overlap i.e. ‘fruit vert’ (Lolita’s ripeness, p.40) and ‘vine leaves in her hair’ (Sibyl’s envy, p. 119), as the colour purple. Wilde clarifies the negative impacts of Dorian’s vanity upon interpersonal relationships through the dull neutrals in his portrait, whereas Nabokov uses the colour red to reflect Humbert Humbert’s psychological state. Quilty’s name holds a comical significance as Nabokov named Quilty to rhyme with ‘guilty’ thus ‘Quilty is guilty’ - Nabokov’s use of rhyme undermines Quilty’s actions which include filming and distributing child pornography, as well as Humbert’s robbery of a girl’s childhood. Humbert refers to Quilty’s exploded ear as ‘a burst of royal purple’ elucidating his discomfort at a gory sight, although Nabokov’s use of the adjective ‘royal’ to describe this implies a subconscious feeling of superiority behind Humbert’s description. Wilde’s use of the same colour ‘the purple hanging from the portrait’ is indicative of the synthesis between Dorian Gray’s external sense of self and internal sense of self as the primary colours symbolising rage (red) and sadness (blue), form the colour purple. In contrast, Nabokov utilises purple as an indication of sexual frustration, the lethargic blue undermining Humbert’s passion, resulting in his association of antagonists with the colour purple. Nabokov characterises Quilty as the antithesis of Humbert; the final synthesis of the characters occur when Humbert murders Quilty: ‘We rolled all over the floor…I rolled over him. We rolled over me. They rolled over me. They rolled over him. We rolled over us.’ Nabokov’s frantic switches of perspective through differing pronouns illustrate the synthesis of Humbert and Quilty, a dogmatic man who considers murder as ‘poetical justice’ (p. 299) and a ruthless ‘red-beast’. Nabokov undermines the doppelganger’s value: he blatantly juxtaposes Humbert as Quilty is, in reality, ‘the alter ego representing complete likeness’ yet Humbert Humbert deliberately withholds Quilty’s significance for most of the narrative, only alluding to Quilty’s role until the end, characterising Quilty as ‘the split personality representing absolute contrast’ (Double Dialogues, 2009). Nabokov utilises ambiguity in the doppelganger to characterise Quilty as a split personality rather than an alter ego, undermining the doppelganger’s value due to the explicit dichotomy between both characters.

As readers, we’re antagonising Quilty yet sympathising with Humbert, whereas we neither sympathise with Dorian nor believe Dorian to be redeemed in violently stabbing his disfigured portrait. H.H.’s murder weapon is described as “snugly wrapped in a white woollen scarf…stock checked walnut”. Nabokov uses sensory imagery of a ‘white woollen scarf’ to describe Humbert’s weapon, a biblical allusion to the idiom ‘a wolf in sheep’s clothing’ as Humbert believes he is redeemed by murdering Quilty but truthfully, the act of murdering Quilty does not morally nor judicially redeem him of the innocence that was robbed from Dolores; Wilde’s description of Dorian’s knife, with which he kills Basil Hallward and (metaphorically) himself, is brief: “It was bright, and glistened” Wilde creates a surreal tone in describing the knife as almost iridescent with the adjective ‘bright’ and the verb ‘glistened’ to describe the reflection of light, the image is beautiful despite knowing it is a murder weapon, reflecting Dorian’s life.

To conclude, I will critique interpretations regarding the intersection between aestheticism and morality in both literary works: an essay by Patrick Duggan regarding this intersection in The Picture of Dorian Gray, an essay regarding this intersection in Lolita by Jennifer Elizabeth Green and an essay comparing the intersection between aestheticism and morality in Lolita and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Predrag Kovaçević. Duggan asserts that The Picture of Dorian Gray is ‘an allegory about morality meant to critique rather than endorse the obeying one’s impulses’ which, in consideration of Dorian Gray’s characterisation as a ‘modern narcissist’ (Kovaçević, 2017), is a strong proposition. Nabokov writes in his afterword for Lolita, he ‘detests symbols and allegories’ thus the story of Humbert Humbert is not an allegory; Pinder supports Duggan’s proposition in her essay, arguing that the floral arrangements reflect Dorian’s surrender to his sensory temptations brought about by Lord Henry’s encouragement to indulge in these sensory temptations (Floral Arrangements in Dorian Gray, 2018). If we are to perceive Lord Henry as the catalyst for Dorian’s modern narcissism, Duggan’s proposition would be futile however Dorian’s narcissism is almost entirely based on his objective perception of himself; Wilde maintains this throughout his novella which leads us to believe Wilde intended this. Kovaçević, comparing Nabokov and Wilde, argues the reasoning behind Wilde’s attention to the moral aspects of the novel stems from Wilde’s literary philosophy that life imitates art and thus art, once reflected in life, should make life beautiful (p.25); Wilde was said to have lived his life as if it were a work of art. In light of this view, Nabokov’s labelling of Wilde as a ‘rank moralist’ would ring true (Playboy, 1964). Kovaçevic then goes on to argue that Nabokov’s literary philosophy juxtaposes that of Wilde’s thus ‘Nabokov is completely disinterested in the idea of art’s influence on life’. I agree with Kovaçevic however I disagree with Kovaçevic’s reasoning behind this, Kovaçevic concludes that it’s due to the period within which Nabokov wrote. Kovaçevic highlights the primary coinciding characteristic of H.H and Dorian Gray: narcissism, referring to H.H. as ‘a postmodern narcissist’ and Dorian Gray as a ‘modern narcissist’, which ‘reflects the deeper split between modern and postmodern aestheticism’ – Nabokov’s primary intent upon writing Lolita was to deceive – as I mentioned before (Nabokov, Lectures on Literature) thus Nabokov must have foreseen this characterisation of Humbert otherwise it is that Nabokov did not intend for the novel to be written in the postmodern period. However, the latter option is unlikely. It’s plausible that Nabokov did preempt this characterisation of H.H. and didn’t preempt the socio-cultural impact of Lolita. Kovaçevic defends his proposition with the notion that the postmodern period values aestheticism significantly more than ethics: “aesthetics has risen above ethics to the point of becoming the very purpose of life itself”. I believe this conclusion to be too general, as the boundary between aestheticism and morality is not utterly blurred and remains explicit in day-to-day life thus, Kovaçevic’s proposition is made moot as Nabokov’s characterisation of Humbert Humbert was intentional. Thus Nabokov further inoculates the reader in his postmodern, narcissistic character of Humbert Humbert. But Nabokov did not preempt the contemporary socio-cultural impact of Lolita, despite the novel being era-defining and the several cultural and social references made to Lolita to this day. Green argues this in her essay, in which she defends the novel with the excuse that Nabokov could not have preempted the contemporary cultural impact of Lolita and we must ‘see through our contemporary cultural constructions’ of Lolita. Since Green’s publication of her essay, the cultural constructions surrounding Lolita are elucidated exponentially further in popular culture, so much that the aestheticism in Lolita significantly outweighs the novel's morality. However, the contemporary cultural impact of Lolita upon the publication of Green’s essay in 2006 placed significant bias toward the aesthetics behind Lolita rather than the novel's morality, due to the two film adaptations of Lolita thus, Green’s proposition is arbitrary. In Green’s defence, the bias towards the aestheticism of Lolita in popular culture could stem from the two film adaptations of Lolita; Nabokov perpetuated this bias, writing the screenplay for Kubrick’s film adaptation of Lolita and contributing to the creation. Nabokov was aware of Lolita’s sociocultural impact to an extent, thus it isn’t illogical to hold Nabokov accountable for Lolita’s sociocultural impact, rather than claim that Nabokov did not preempt the sociocultural impact, as Nabokov states explicitly in Lolita’s afterword: “Lolita has no moral in tow” (p. 314). Therefore, Nabokov indeed intentionally blurs the boundaries between aestheticism and morality to inoculate the reader against Humbert Humbert’s solipsism and paedophilia towards Dolores Haze due to Nabokov’s blatant disregard for the socio-cultural impact of Lolita whereas Wilde, paying attention to the socio-cultural impact of his novella, utilises aesthetics to illustrate Dorian’s vanity and his surrender to sensory indulgences.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Toffler, Alvin. “A Candid Conversation with the Artful, Erudite Author of LOLITA.” Geneva: Playboy Magazine, January 1964. Print.

Nabokov, Vladimir V and Fredson Bowers, “Lectures on Russian Literature”. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich/Bruccoli Clark (1981). Print.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Picture of Dorian Gray” London: Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, July 1890. Print.

Nabokov, Vladimir. “The Annotated Lolita” United Kingdom: Penguin Publishing, 27th July (2000). Print.

Faurholt, Gry. “Self as Other: The Doppelgänger | Double Dialogues.” Issue 10. Denmark: Aarhus University, (2009). Print.

Pinder, Morgan. “The Monstrosity of Orchids – Floral Arrangements in Dorian Gray” The FrankenPod: WordPress, (2018). Article.

Duggan, Patrick. “The Conflict Between Aestheticism and Morality in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’” (2009) Boston: Boston University of Arts and Sciences. Article.

Kovačević, Predrag S. "Language, art, and the (social) body in modern and postmodern aestheticism: A comparison of Wilde and Nabokov." (2017) pp19-37. Article.

Green, Jennifer Elizabeth, "Aesthetic Excuses and Moral Crimes: The Convergence of Morality and Aesthetics in Nabokov's ‘Lolita’." Thesis, Georgia State University, (2006).

Recommended resources

iHeartRadio, ‘Lolita Podcast’, Jamie Loftus (2020). Podcast.

Random House Trade Paperbacks, ‘Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books’, Azar Nafisi (2003). Paperback.

YouTube, ‘the lolita resurgence … when history repeats itself’, Jordan Theresa (2021). Video.

YouTube, ‘we need to talk about Lolita | Lola Sebastian’ , Lola Sebastian (2019). Video.

YouTube, ‘The Nymphet Femme Fatale (As Popularized By Misreadings of Lolita)’, Yhara zayd (2021). Video.

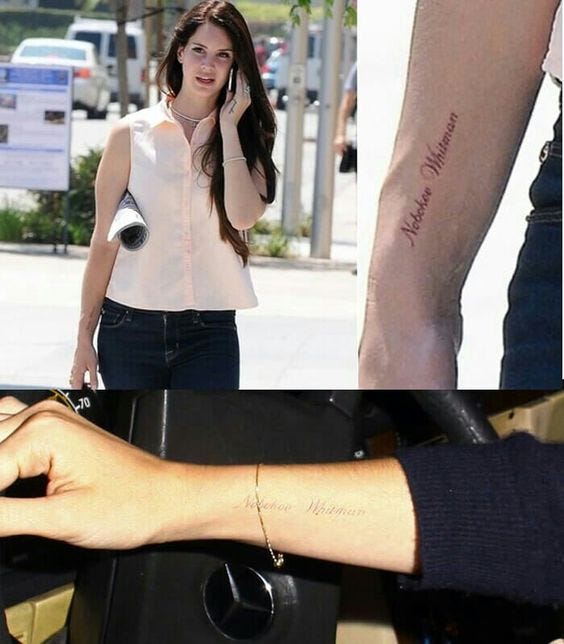

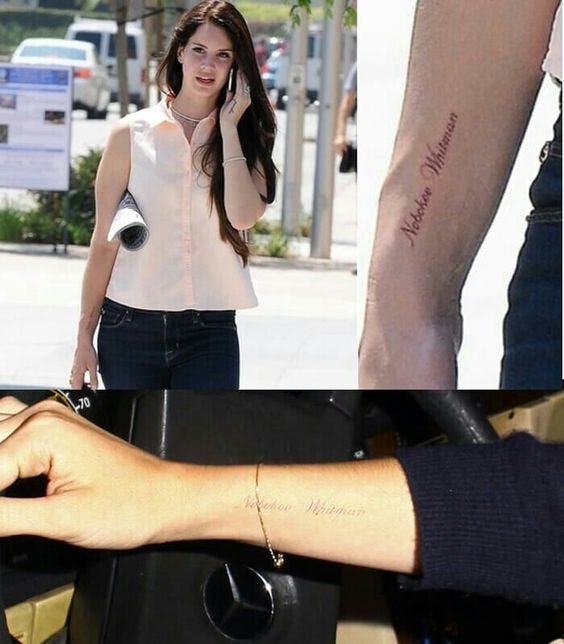

Lana Del Rey, Lolita and Nymphettes

The songs directly refer to Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and how the Born To Die album borrows from Nabokov’s novel.